When I exercise, I choose to run outside. It could be 100 degrees or 35 below zero and I will still lace up and hit the pavement. I avoid gyms because I am convinced that regular time spent outside is good for me. When I sit inside or stand behind a counter all day, I cringe at the thought of wasting even 30 minutes of my breath in a gym; I gulp my breaths, and the finest air is outside.

That being said, I’m not a hardcore outdoors person. I like living in cities with lots of people, opportunities, ideas and 10pm happy hours. I have no desire to live on a farm. I take to heart the words of Jim Gaffigan, who quips, “The happiest camper is the one leaving the campsite.” When I’m outdoors, I love the sights and smells of plants, animals and freshwater, but camping to me feels a lot like chores during valuable free time. I escape outside, but I live in a city.

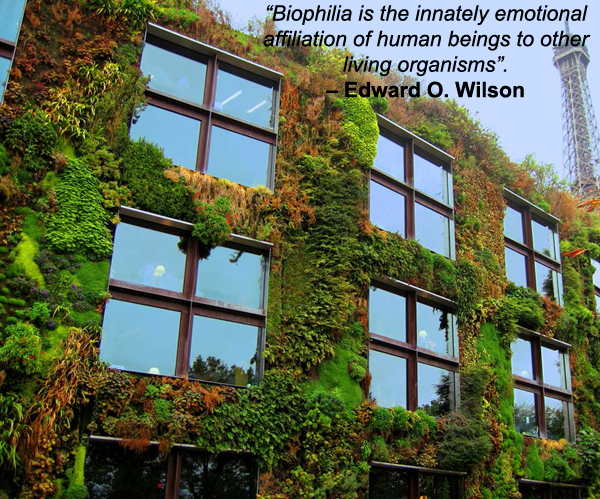

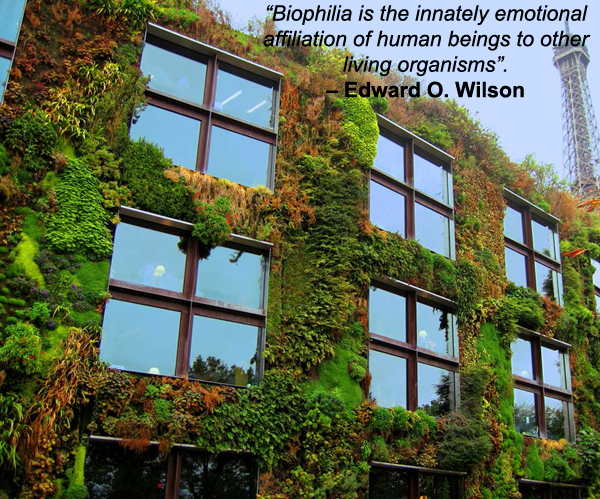

There’s something to be learned from this feeling toward natural environments. For much of human history, our ancestors lived and died surrounded by green environments. Our bodies and our minds are built from copies of their surviving genes, so we are prepared for those same kinds of environments. The steel and concrete worlds that many of us inhabit now are mismatched with our tendency toward biophilia, or our affinity to life in its natural form.

Now, without forsaking civilization for the life of a hunter-gatherer, or without tearing down all the buildings and ripping up the roads, how can we use this supposed affinity for green to better our lives? Is it possible to both live in a city and experience the natural environment?

I think so. Live near green space. Fight for its development or against its destruction. Here’s why.

New research from Mathew White and his colleagues sheds light on the psyvchological benefits of green space. Generally, these researchers are interested in population level estimates of well-being. Because much research focuses on factors associated with negative outcomes, these researchers wanted to know what is associated with flourishing. They asked a simple question :

Does living near urban green space contribute to psychological well-being compared to other factors?

Cross-sectional research (i.e., snapshots of a population at one time) suggests that it does, but that research is confounded by time-stable characteristics, namely, personality. It could be that happy people move to areas where there is a lot of green space. To control for this, White and company analyzed longitudinal data of over 10,000 people from an 18-year panel survey, the British Household Panel Survey. They were able to compare the self-reported psychological health of the same people at different points in time alongside other known contributing variables such as education, employment, marriage and local crime.

How did they know people lived near green space?

Generalized Land Use Database (GLUD)

- Classifies land use statistics

Lower Layer Super Output Areas (LSOA)

- Standard geographic unit used to report small area statistics, encompasses area of 1500 people

- Classified into nine categories: green space, domestic gardens, fresh water, domestic buildings, nondomestic buildings, roads, paths, railways, and other

Combined green space and gardens

Only urban residents

How did they determine the mental health of 10,000 people?

12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ)

- Widely used and reliable self-assessment screening tool to aid clinical diagnosis of mood disorders such as anxiety and depression

- Asks how the “past few weeks” compare with “usual” in terms of six positive and six negative states

- “not at all” or “no more than usual” to “rather more than usual” or “much more than usual” (0 to 3)

- 0 (very low mental distress) to 3 (very high mental distress)

How did they determine “well-being?”

“How dissatisfied or satisfied are you with your life overall?”

- 1 (not satisfied at all) to 7 (completely satisfied)

What did they control for?

English Indices of Deprivation

- Income (based on social benefit data)

- Employment (based on unemployment data)

- Education (based on school performance, participation in higher education, and qualifications of working age adults)

- Crime

- Age

- Education (holding a diploma or degree)

- Marital status (including living with a partner)

- Number of children living at home

- Work-limiting health status

- Labor market status (employed, self-employed, unemployed, retired, in education or training, family caregiver)

- Residence type (detached, semidetached, terraced, flat, other), household space (rooms-per-person ratio)

- Commute length in minutes

Area-level data were distributed to an individual’s BHPS profile.

What did they find?

For 10,000+ people in England, the average score on the GHQ was 1.92 with a margin of error of ± 0.02 points. For every 1% increase in green space, there was a 0.0043 decrease in GHQ.

The average response for life satisfaction was 5.2 with a margin of error of ± 0.01 points. For every 1% increase in green space, there was a 0.0043 increase in self-reported life satisfaction.

To put this into perspective, people in this population lived in areas composed of, on average, 64% green space. Living in areas composed of 81% green space (1 standard deviation above the average) compared to living in areas composed of 48% green space (1 standard deviation below the average) was associated with a 0.14 point reduction in scores on the GHQ and a 0.07 increase in life satisfaction.

The benefits of the chosen analysis allowed for comparison to other factors associated with mental health and well-being. Using the same comparisons between living in areas with green space 1 standard deviation above and below the average amount, the reductions in scores on the GHQ were:

- 35% as large as those associated with being married

- 12% as large as those associated with being employed

The associated increases in life satisfaction were:

- 28% as large as those associated with being married

- 21% as large as those associated with being employed

These effects aren’t large, but they are meaningful considering that no correlations with were found between the GHQ nor life satisfaction and living in areas with lower crime rates or in households with higher incomes.

Since not all potentially influential factors were controlled for in the analysis, causality cannot be assumed. These finding should be considered in the context of other research on the effects of green space on well-being. I’ve written on some of this research before, and I hope to tackle more of it in the future. Visit here for another great blog on this topic.

Now, when you get a chance, go outside. It’s good for you.

References

White, M. P., Alcock, I., Wheeler, B. W., & Depledge, M. H. (2013). Would you be happier living in a greener urban area? A fixed-effects analysis of panel data. Psychological science, 24, 920-928.